Solar panels, currently touted around the world as an important means of reducing carbon emissions, have a lifespan of up to 25 years.

Experts warn that this means billions of panels will eventually have to be scrapped and replaced. “The world’s installed solar capacity exceeds one terawatt. Typical solar panels are about 400W, so if you add rooftops and solar farms, there could be as many as 2.5 billion solar panels.” dr. said Deng Rong, Australia’s new solar panel recycling expert at the University of South Wales. According to the UK government, there are tens of millions of solar panels in the UK, but not enough infrastructure to process and recycle them.

Energy experts are calling on governments to take urgent action to avert a looming global environmental disaster. “By 2050 we will face mountains of waste if we don’t start building recycling chains now,” said Ute Collier, deputy director of the International Renewable Energy Agency.

“We’re making more and more solar panels, which is great, but what do we do with the waste?” she asked.

Recycling

A big step is expected at the end of June, when the world’s first factory dedicated to the complete recycling of solar panels will be officially opened in France.

ROSI, a company specializing in solar energy recycling with a factory in the Alpine town of Grenoble, hopes to recover and recycle 99% of the plant’s components. In addition to recycling glass panels and aluminum frames, the new facility can recycle almost all valuable materials in panels, such as silver and copper, which are often some of the most difficult materials to obtain.

These rare materials can be reused and recycled to create new, more powerful solar cells. Traditional solar panel recycling methods recover most of the aluminum and glass, but the glass in particular is of relatively low quality, according to ROSI.

Glass obtained using these methods can be used to make tiles or mixed with other materials to make asphalt, but cannot be used in applications that require high-quality glass, such as new solar panels.

Boom period

ROSI’s new factory opens amid a solar panel installation boom.

Global solar energy production will grow by 22% in 2021. Around 13,000 solar panels are installed every month in the UK, most of which are on the roofs of private homes.

In many cases, solar PV systems become relatively uneconomical before they reach their expected lifetime. New, more efficient designs are introduced regularly, meaning it can be more economical to replace solar panels that are only 10 or 15 years old with newer versions.

Collier said if current growth trends continue, the number of abandoned solar panels could be significant. “By 2030 we estimate that we will generate 4 million tonnes (of waste) which is still manageable, but by 2050 the world could end up with more than 200 million tonnes.”

To put this into perspective, 400 million tons of plastic are produced worldwide today.

Recycling challenges

The reason for recycling solar panels is so little that until recently there wasn’t much waste available to recycle and recycle.

The first generation of solar panels for homes have now reached the end of their life. Experts say swift action is needed as the units are expected to be phased out.

“Now is the time to think about it,” Collier said. Nicolas Defren says that France has become a leader among European countries in the treatment of photovoltaic waste, the item that converts light energy into electricity. His organization Søren works with ROSI and other companies to coordinate the removal of solar panels across France. “The biggest one (we removed) took us three months,” Defreny recalled.

His team at Solon has tried different ways to recycle what it collects: “We’re trying everything to see what works.”

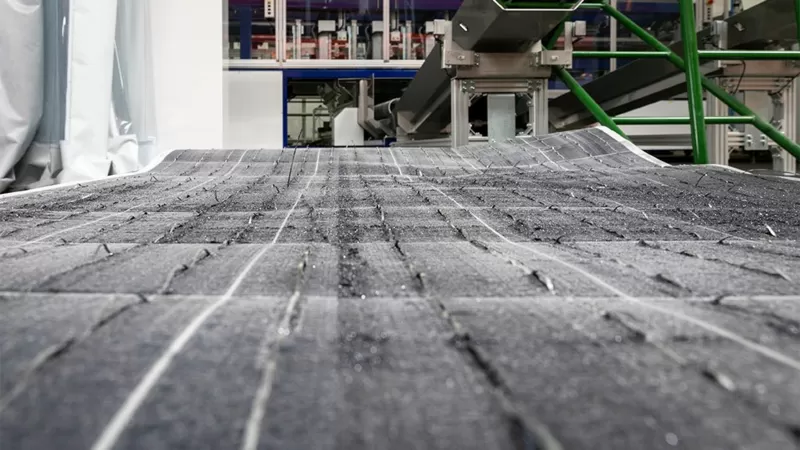

At ROSI’s state-of-the-art plant in Grenoble, solar panels are carefully disassembled to recycle the valuable materials inside, such as copper, silicon and silver. Each solar panel contains only small fragments of these expensive materials, and these fragments are so intertwined with other components that it has not been economically possible to separate them until now.

But given the enormous value of these precious materials, Devren said that extracting them efficiently could be a game-changer. “More than 60 percent of the value is in 3 percent of the solar panel’s weight,” he said.

Søren’s team hopes that nearly three-quarters of the materials needed to make new solar panels in the future, including silver, can be recovered from unused solar cells and reused to speed up the production of new panels. Currently, there is not enough silver to make the millions of solar panels needed to transition away from fossil fuels, de Fresner said: “You can see where the production bottlenecks are, that’s silver.”

Meanwhile, British scientists have been trying to develop ROSI-like technology.

Last year, researchers at the University of Leicester announced that they had discovered how to extract silver from solar cells using a saltwater solution. But so far, ROSI is the only company in this field that has scaled up its operations to an industrial level.

In addition, the technology is expensive. In Europe, the solar panel importer or manufacturer is responsible for disposing of the solar panels when they become unusable. Many people choose to shred or shred their waste, which is much cheaper. De Frena admits that intensive recycling of solar panels is still in its infancy. Soren and his partners recycled nearly 4,000 tons of French solar panels last year. But there is potential to do more. He has made it his mission. “The weight of all the new solar panels sold in France last year was 232,000 tons, so when they wear out after 20 years, that’s how much I have to collect every year.

“When that happens, my personal goal is to ensure that France becomes a world leader in technology.”