Sometimes you can feel like the world is burning.

Europe is experiencing a heat wave that has been dubbed the “hell week” in Italy.

Temperatures above 50°C have been recorded in China and the US, where body bags filled with ice are used to cool hospital patients.

The UK just had the hottest June in its history. And in 2022 this country recorded over 40°C for the first time.

Europe’s heat wave last year caused an estimated 60,000 deaths.

Not surprisingly, the United Nations warns that we now live in the era of “global boiling.”

“I think it’s really important to realize that it’s not something distant or in the future. We’re seeing it now,” says Lizzie Kendon professor of the UK’s National Weather Service.

So what does climate change mean for our bodies and our health?

I tend to collapse into a sweaty puddle when it’s hot, but I’ve been invited to take part in a heat wave experiment.

Professor Damian Bailey, from the University of South Wales, wants to give me a typical heatwave experience. We’ll start at 21°C, then turn the thermostat up to 35°C and finally to 40.3°C, the equivalent of the hottest day in the UK.

“You will sweat and your body’s physiology can change considerably,” Professor Bailey warns me.

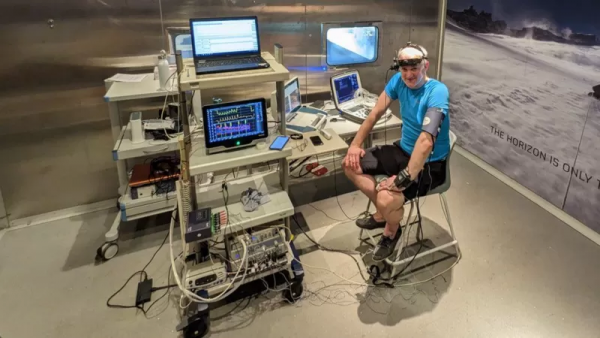

He then leads me into the environmental chamber. It’s a room set up with scientific equipment that can monitor temperature, humidity and oxygen levels precisely.

I’ve been here before exploring the effects of cold.

But the shiny steel walls and heavy door make me feel like I’m looking into my oven.

The temperature starts at a perfect, balmy 21°C when Professor Bailey gives the first instruction to “remove everything completely.”

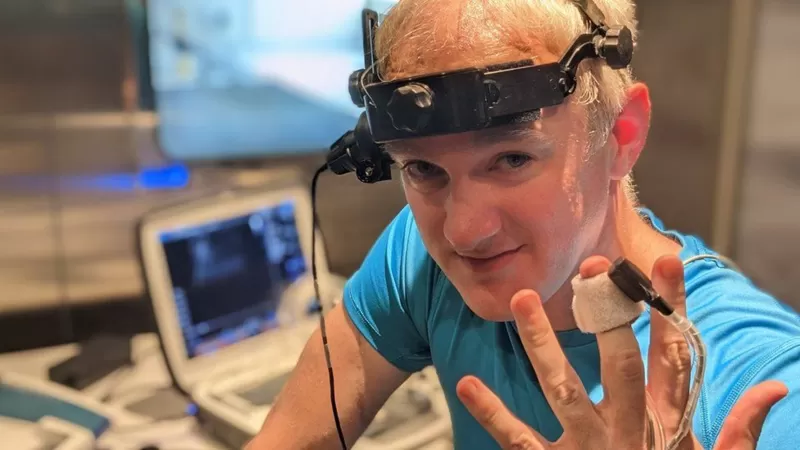

Then I’m hooked up to a dizzying array of gadgets that track the temperature of my skin and internal organs, my heart rate and blood pressure.

A huge mouthpiece analyzes the air I exhale and an ultrasound inspects the blood flow to my brain through the carotid arteries in my neck.

“Blood pressure is working fine, heart rate is working fine, all physiological signals at this point indicate you’re in great shape,” Professor Bailey tells me.

We have a quick brain exercise, memorizing a 30-word list. The fans come on. The temperature starts to rise.

My body has the simple goal of keeping the temperature around my heart, lungs, liver and other organs at about 37°C.

“The thermostat in our brain, or hypothalamus, is constantly testing the temperature. Then it sends all those signals to maintain that,” Bailey says.

We took a break at 35°C to make more measurements. It feels warm now. It’s not uncomfortable and I’m sitting relaxed in a chair, but I wouldn’t want to work or exercise in here.

Some changes in my body are already clear. I am redder. Damian is too, since he is in here with me. This is because the blood vessels near the surface of my skin are opening up to make it easier for my warm blood to lose heat to the air.

I’m also sweating, not dripping, but positively glowing, and when the sweat evaporates, that cools me down.

So we climb to 40.3°C and now I feel the heat engulfing me.

“It’s not linear, but exponential. Five degrees more doesn’t seem like much, but psychologically it’s a much bigger challenge,” says Professor Bailey.

I’m glad we’re not going any higher. When I run my hand across my forehead, it’s soaked. It’s time for a retest.

When I throw my sweaty clothes on the floor, I towel dry and step back on the scale. I am surprised to learn that I have lost more than a third of a liter of water during the course of the experiment.

The cost of opening all those blood vessels near my skin to lose heat is also clear. My heart rate has increased significantly and at 40 °C it is pumping one liter more blood per minute around my body than at 21 °C.

This extra strain on the heart is why there is an increase in deaths from heart attacks and strokes when temperatures soar.

And as blood rushes to my skin, it is my brain that loses out. Blood flow decreases and so does my short-term memory.

But my body’s main goal, to keep my core temperature around 37°C, has been achieved.

“Your body is working pretty well to try to defend that core temperature, but, of course, the numbers suggest that you were not the same beast at 40°C as you were at 21°C, and that’s in less than an hour,” says the professor.

Humidity as a factor

In my experiment only the temperature varied, but the other crucial factor to consider is humidity, the amount of water vapor in the air.

If you’ve ever felt really uncomfortable on a muggy night, then you can blame it on humidity, as it affects our body’s ability to cool itself.

Sweating is not enough. Only when this sweat evaporates into the air does it give us the cooling effect.

When there are already high levels of water in the air, it is more difficult for the sweat to evaporate.

Damian kept the humidity at 50% (not unusual in the UK), but a team at Pennsylvania State University tested a group of young, healthy adults with different combinations of temperature and humidity.

They were looking for the moment when core body temperature began to rise rapidly.

“That’s when it becomes dangerous. Our core temperature starts to rise and organ failure can occur,” says researcher Rachel Cottle.

And that dangerous point is reached at lower temperatures if humidity is high.

The concern is that heat waves are not only becoming more frequent, longer and more severe, but also more humid,” says Cottle.

The expert notes that last year India and Pakistan were hit by a severe heat wave with critical temperatures and high humidity. “It’s a ‘now’ problem, not a future one,” she says.

The human body is designed to operate at a core temperature of around 37°C. We get dizzy and become more susceptible to fainting when it approaches 40°C.

High core temperatures damage our body tissues, such as the heart muscles and the brain. There comes a point when it becomes deadly.

“When the core temperature rises to 41°C – 42°C, we start to see significant problems that, if left untreated, can cause the death of the individual from hyperthermia,” says Bailey.

This phenomenon, known as heat stroke, is a medical emergency.

People’s ability to cope with heat varies, but age and poor health make us more vulnerable. Temperatures we once enjoyed during the vacations can be dangerous at another time in life.

“You’ll leave the lab today with a smile on your face. All these statistics tell me you’ve risen to the challenge and done a good job,” Bailey says.

Old age, cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, dementia and certain medications mean the body is already working harder to keep functioning, so it is less able to respond to heat.

“Every day is a physiological challenge for them. When you add more heat and humidity, sometimes they can’t overcome that challenge,” the specialist adds.

How to deal with it?

Many of the tips for coping with the heat are obvious and well known: stay in the shade, wear loose clothing, avoid alcohol, keep your home cool, don’t exercise during the hottest hours of the day and stay hydrated.

“Another tip is to try not to get sunburned. A mild sunburn can override the ability to thermoregulate or sweat for up to two weeks,” says Professor Bailey.

But dealing with the heat is something we should all get used to.

Without action on climate change, Professor Lizzie Kendon said the hottest day of the summer in the UK could rise by 6°C under a high emissions scenario.

“That’s a big increase by the end of the century,” she says.